| This

page weaves together excerpts from a number of accounts of the making

of Genevieve. To read about the production of Genevieve from

the perspective of The Veteran Car Club, read Elizabeth Nagle's account of the

Club's dealings with the producers

here. |

| Following

text

from Quentin Falk's "The Golden Gong: Fifty Years Of The Rank Organisation,

Its Films And Its Stars" © Columbus Books 1987; (currently out of print).

Stills courtesy BFI Films: Stills Posters and Designs |

| Quentin

Falk: Motorists

negotiating country lanes near Moor Park Golf Club in Hertfordshire, north

of London, must have been astonished suddenly to find signposts proclaiming

"Brighton: 6 miles." A local copper was positively bewildered when,

glancing out of his bedroom window one morning, he saw another sign,

"Beware: Cattle Crossing," which seemed to have sprung up mysteriously

overnight. It was in the gathering winter of 1952-3, and one of Rank's most

successful, and enduring, films had begun shooting. |

| That

Genevieve even made it before the cameras was a triumph for the

persistent 39-year-old producer-director

Henry

Cornelius. South African-born and

Sorbonne-educated, "Corny," as he was known, first learned his craft

as an assistant to the great French director René Clair. As director, he met

had made the popular Ealing comedy Passport to Pimlico (1949). Following

text

from Sir Michael Balcon's "Michael Balcon presents... A Lifetime of Films"

©

Hutchinson & Co., 1969

(currently out of print).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sir Michael Balcon:

Henry Cornelius had left Ealing and set himself up as an independent.

After much frustration he managed to get financial support for a film,

The Galloping Major, a good comedy idea of a small community investing

in a racehorse.

It made an appealing film but,

inappropriately for a racehorse, it was a bit of a slow starter and

consequently Corny had difficulty in setting up his second film. Pocketing

his pride, he returned to me with an outline story, by no means fully

developed, by Bill Rose, and I knew at once that it could not miss.

I was now faced with a moral dilemma. Our own schedule of

films of was arranged and if I took Corny back it would mean displacing another

director, an idea which would not have proved popular for good and valid

reasons. Although Corny was immensely popular with his ex-colleagues at Ealing,

he had left of his own volition and, by the way, it was very rare for anybody to

leave Ealing.

As I was then a director of The Rank Organisation, I sent

Corny to Earl St. John, in charge of production at Pinewood. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quentin

Falk: Armed

with the script by William

Rose, an American, Corny went out to persuade Earl St. John to back the film on behalf of Rank. St. John,

confronted with this whimsical comedy about two young couples who plan to race

their old crocks home from the London-Brighton veteran car rally, was

incredulous. "If we made that sort of film, I'd get the sack and, frankly,

I can't afford to lose my job," he told Corny. But

the filmmaker just would not take "no" for an answer and returned two or three

more times to work on St. John. Finally

the Organisation's executive producer asked what the budget would be. The answer

was £115,000 -- not a vast amount, he admitted, but he'd still have to get

board approval. |

Rank

eventually agreed to provide 70 percent of the investment as long as Cornelius

could find the remaining 30 percent, which he managed thanks to the involvement

of the government-sponsored "merchant bank," the National Film Finance

Corporation (NFFC). Rank

eventually agreed to provide 70 percent of the investment as long as Cornelius

could find the remaining 30 percent, which he managed thanks to the involvement

of the government-sponsored "merchant bank," the National Film Finance

Corporation (NFFC).Following

text

from Christopher Challis's "Are They Really So Awful? : A Cameraman's

Chronicle" © Christopher Challis 1995. This book is

available at Amazon and is highly recommended.

and is highly recommended. |

Christopher

Challis: ...The

Rank Organisation agreed to back it, but with the minimum investment, and on

condition that Henry Cornelius put up the completion money himself. In order to

do this, he had mortgaged his house and sold every tangible asset and here he

was, with the absolutely minimum of finance, on the verge of turning his dream

into a reality. Christopher

Challis: ...The

Rank Organisation agreed to back it, but with the minimum investment, and on

condition that Henry Cornelius put up the completion money himself. In order to

do this, he had mortgaged his house and sold every tangible asset and here he

was, with the absolutely minimum of finance, on the verge of turning his dream

into a reality. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

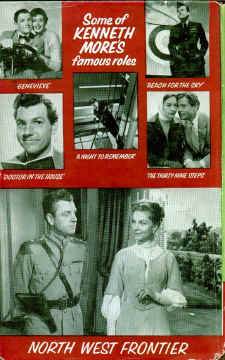

| Quentin

Falk:

Casting

was to prove perhaps the key to the film's eventual success. Playing Alan and

Wendy McKim were to be John Gregson, who had already featured in some Ealing

comedies, and Dinah Sheridan, the English rose of Where

No Vultures Fly (1951). |

|

|

|

|

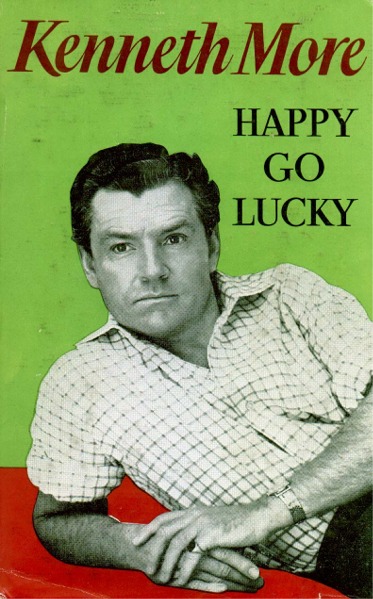

Kenneth

More was, at the time, wowing West End theater audiences in Terrence Rattigan's The

Deep Blue Sea.

"Critics hailed me almost as an overnight discovery," he

reflected, "conveniently forgetting I was already 38 and I'd been working

in the theater for nearly twenty years." More had also been seen in a

handful of small screen roles, including Scott of the Antarctic (1948). Kenneth

More was, at the time, wowing West End theater audiences in Terrence Rattigan's The

Deep Blue Sea.

"Critics hailed me almost as an overnight discovery," he

reflected, "conveniently forgetting I was already 38 and I'd been working

in the theater for nearly twenty years." More had also been seen in a

handful of small screen roles, including Scott of the Antarctic (1948).Following

text

from Kenneth More's "Happy Go Lucky" ©

Kenneth More 1959, Robert Hale Ltd.

(currently out of print). Mr.

More is a wonderful storyteller, but his versions of events are often at odds

with the recollections of others.

Kenneth More:

One evening after the performance of The Deep Blue Sea, I was in my

dressing room at the Duchess when a message came up from the stage door that Mr.

Cornelius wanted to see me. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Cornelius?" I asked. "Cornelius?" I asked.

"Yes.

Henry Cornelius."

The name meant nothing to me. Suddenly I remembered; he had

directed that test for Scott of The Antarctic at Ealing.

[Quentin Falk

points out that

More had played a "spit and a cough" in the director's The

Galloping Major a year earlier, so it seems highly unlikely that the name

Henry Cornelius would "mean nothing" to More!]

Corny came up. Born in South Africa and educated in Germany and France, he

was the enfant terrible of the film world of pre-Hitler Berlin. He

worked on The Drum and The Four Feathers as film editor, and

since our last meeting had directed the top Ealing comedy Passport to

Pimlico. Now he had formed his own

independent company.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In The Deep Blue Sea we had won such ecstatic reviews, and flattery

from visitors had become such a routine thing, that I fully expected him

to say: "What wonderful performance tonight!" But when I asked him if he had been out front, he said:

"No."

"You've seen the play already then?"

"As a matter-of-fact I haven't. This sort of show isn't

my cup of tea at all."

I was at a loss. I couldn't help asking: "What is it you

want?"

"I'd like you to be in a film I'm making," he said.

"The test you did for Scott showed me that you have the qualities I

need."

He

went on to explain that he had been offered the outline of a story which he

liked so much that he snapped it up within 48 hours. "The plot," said

Corny, "centers on the veteran cars annual rally from London to

Brighton."

"What do you want me to play?" I asked.

"Ambrose Claverhouse -- brash, bouncy, girl-chasing; an

extrovert."

"Comedy?"

"Character comedy."

|

|

|

|

|

Ambrose, Corny said, is an advertising agent who rides in

ancient barrel-bonneted Dutch Spyker in the rally. His intentions where women

are concerned are far from honourable. He believes in taking a different girl

with him on every week-end trip. On this occasion his companion is a model,

Rosalind Peters. Ambrose also has a friend, a young barrister named Alan McKim,

who goes to Brighton with his wife Wendy in "Genevieve," a 12

horsepower Darracq made in Paris in 1904. All

four get to Brighton, but Ambrose and Alan quarrel, the outcome being a 100

pound wager as to which of them can drive back to Westminster Bridge first.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| "The return journey," Corny enthused, his eyes

sparkling, "is packed with laughs; water splashes, sheep blocking the road,

children holding up the cars by dawdling on the zebra crossing, and so on.

Ambrose and Alan practically go crazy with excitement." [Dinah

Sheridan says

the children on the zebra crossing was a last-minute inspiration on the part of

Henry Cornelius.]

He

gave me the script. I put it on my knee, glanced at the title -- Genevieve

-- and started reading.

|

|

|

|

|

"We'll be doing it in Technicolor at Pinewood,"

Corny went on, persuasively. "Larry Adler is composing the music."

I hadn't finished the second page before I realized that the

film was for me. "This is marvelous," I said. "I've got to be in

it!"

"Of course," said Corny. "And you will

be too. I'm a very determined man. The part has been written with you in mind."

[Dinah

Sheridan says

the director's first choice for the part was Guy Middleton]

Then I started to think of the obstacles, all the difficulties

that would crop up. "I've just been married," I said. "We're

moving house at any moment and I'm appearing in this play!"

|

|

|

|

|

|

But every objection I raised, Corny knocked down.

Moving house? The best removal firm in London would be called

in; it would lay on a fleet of vans and we wouldn't have to lift a finger.

Getting from the studio to the theater? He would personally arrange for a

superfast car to do the journey at record speed.

"But what about [More's wife] Bill?" I asked.

"How will she manage on her own? I won't have time to see anything of her

at all if I do a film as well as a play."

"Don't worry," said Corny blandly. "She can

visit you at the studio. We serve lovely meals in the canteen."

Lovely meals in the canteen!

"Anyway," said Corny, "come and have lunch

tomorrow with me and Kay Kendall. She is to be your girlfriend, Rosalind, in the

film".

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

"Quentin

Falk: The vivacious Kay Kendall

(born Justine McCarthy), though only 26, had made an earlier bid for

stardom in the film London Town.

Kenneth More:

As

far as Katie was concerned, it was to be her second bid for stardom. Once the

youngest-ever member of the Palladium chorus line,

she starred at the age of 17

in London Town, perhaps the biggest screen flop of all time. She had

seemed set for a golden career; then suddenly everything was finished. It was

the most shattering experience anyone could have. But she had guts; she went

into rep, did TV and gradually charmed her way back into the films.

|

|

|

|

|

The three of us met in Rule's, in Maiden Lane, for the maddest

lunch I can remember. Corny opened his briefcase and brought out sheets and

sheets of foolscap on our "family backgrounds." I, as Ambrose, was the

son of a kidney pill manufacturer; Katie learned that Rosalind's grandfather had

crossed the Alps at the age of three. The three of us met in Rule's, in Maiden Lane, for the maddest

lunch I can remember. Corny opened his briefcase and brought out sheets and

sheets of foolscap on our "family backgrounds." I, as Ambrose, was the

son of a kidney pill manufacturer; Katie learned that Rosalind's grandfather had

crossed the Alps at the age of three.

We roared with laughter. We were in fits.

"What on earth does it matter who our relatives

were?" we asked. "Either you want us to play these parts or you

don't!"

But Corny didn't work like that. He was very painstaking. He

believed in what I suppose could be called The Method. But Corny didn't work like that. He was very painstaking. He

believed in what I suppose could be called The Method.

We must have had one glass too many of the burgundy because

Katie and I ended the meal by promising to do the film.

For me, Genevieve was a bid for stardom too. I

remembered what Bill had told me once, when I confided in her my hopes for the

future.

"You'll never be a star," she said, "until

you've had a part with real personality in it."

Was Ambrose Claverhouse, the hearty terror of the highways,

the answer?

I signed a contract with Corny for £2,500.

The

snag that probably none of us fully realized when we entered the film so gaily

was that three-quarters of the shooting was on outdoor location. The 57 day

production schedule lasted from October to February, right through some of the

bitterest weather of the year.

Christopher Challis:

George Gunn [a Technicolor

representative] had persuaded Henry that, in spite of the money problem, the

extra cost of filming in colour was more than worthwhile as, at that time, it

was still a great attraction at the box office.

|

|

|

Planned to be filmed

almost entirely outdoors... weather was obviously a big hazard and Henry

explained that he could not afford to wait for ideal conditions. 'If there

is enough light to get a bare exposure, I just have to shoot. I know it's

asking a lot, but there is no other way I can make the picture.' Kenneth More:

Corny very cunningly solved

the lighting problem by taking his own special brand of sunshine with us

in the form of a generator and 24 arc lamps. The result was a fantastic

sight. A winding caravan of cars, vans and trucks loaded with 50 tons of

gear blocked the roads and caused traffic chaos. |

|

|

|

|

Christopher Challis:

The traveling scenes in the cars

were resolved by loading the whole unit into in large flat, open trailer,

known as a 'Queen Mary.' It was a relic of the war and had been used to

transport military aircraft. We all piled in - camera, lights, crew and

small generator -- and on the back was perched a mock-up of the car in

which our actors 'drove.' |

|

|

|

|

The whole circus was

at the mercy of the driver in the cab of the Queen Mary, who often proved

difficult to communicate with. Another truck followed with mock-ups of the

other cars, ready to be switched at a moment's notice. For forward-looking

shots, another flat truck was used. The driving cab was removed, further

mock-ups made to disguise what little we saw of the bonnet and a period

steering wheel and windscreen fitted, all of which had to be changed each

time we switched cars.

|

|

| |

|

| Kenneth More:

The genuine London to Brighton route wasn't right for all the

backgrounds we needed so, on the assumption (later proved correct) that only

diehard devotes of the rally would notice, we shot quite a few of the "deep

in the heart of Sussex" scenes in Buckinghamshire, near Moor Park golf

course. When we did venture into Sussex, we littered it with phony

signposts, signs and traffic lights. Motorists were baffled to see

"Brighton 6" on signposts when they thought that the sea was at least

40 miles away. |

|

|

|

We

had a high-spirited time together. Playing Wendy McKim was Dinah Sheridan, the

blue-eyed strawberry blonde who is a keen, hearty motorist. She took a

bone-rattling on African roads in Where No Vultures Fly, but had to admit

that bumping down a cart-track in Kenya in a jeep was paradise compared with the

trip to Brighton in Genevieve. |

| |

|

| Then, of course, there was Katie, who loves fun and laughter.

She lounged around the set, a dazzling vision in tight blue jeans and mules

trimmed with ostrich feathers. For the actual film, Marjorie Cornelius, Corny's

wife, designed for her some superb creations, very elegant, very English, with

enormous floppy hats. |

| |

|

|

Marjorie's costumes for Dinah, I recall, included a dress in

chocolate, coffee and strawberry, which gave the appearance of a very delectable

Neapolitan ice.

My rival in the film, in our grueling, jolting journey was

John Gregson, a burly, tousle-haired Liverpudlian who like myself was in the

Royal Navy during the war, but in minesweepers.

|

| |

|

|

|

Also like me, he had been in that frosty epic, Scott of the Antarctic, though he had taken a shortcut

to success with Whiskey Galore, The Lavender Hill Mob and Angels

One Five. In Genevieve, John achieved the no mean feat of driving

from London to Brighton and back without a full driving license! He took a

course of lessons, but there wasn't time to pass his test before filming began.

In all, he did about 100 miles at the wheel, with the police turning of the

blindest of the blind eyes.

In many respects we enjoyed

ourselves immensely. |

|

|

We had Joyce Grenfell giving an

excruciatingly genteel performance as a hotel manageress. Also, John got a taste

of the penalties of screen fame when audiences believe implicitly in what you

do. We had Joyce Grenfell giving an

excruciatingly genteel performance as a hotel manageress. Also, John got a taste

of the penalties of screen fame when audiences believe implicitly in what you

do.

We were in the Old Kent Road, waiting between takes, when a

little girl of about nine came up and asked him: "Hey, mister, is your name

John Gregson?" |

|

|

John preened himself, admitted that he was indeed John Gregson

and prepared to whip out his fountain pen for an autograph. But little girl

hadn't finished her questions.

"Weren't you in Venetian Bird?"

John nodded.

"And didn't you bash Richard Todd on the back of the

head?"

"Well, yes," John admitted. "That's

right."

|

|

|

"Then I'll never see one of your pictures again as long

as I live!" With that, she swept off.

We had another moment of humour, completely unrehearsed and

certainly not in the script, which all happened because Corny was such a

perfectionist. He had to have everything right. Every single scene had to be

filmed time and time again, just to be absolutely sure.

|

|

| |

|

This wasn't too bad in the studio, but it was perfect hell out

of doors. One morning -- about 7:00 it was, and dreadfully cold -- Kate and I

had to do a shot in which we drove down the road towards the camera.

We

did it once, but Corny wasn't satisfied. We did it again, but that wasn't right;

a hair had got in the gate of the camera. We did it a third time -- and a

fourth. On each occasion, the repeat performance meant driving half a mile back

up the road again and turning round.

The weather grew even worse. A fine penetrating drizzle came

down, soaking us through. We couldn't wear macs or any other kind of protection

because it was supposed to be fine weather.

The more times we kept on doing the journey, the more frozen

and cross Katie became. When we had done the scene for the fifth time, and Corny

said: "Let's have just one more!" Katie grabbed the parasol which was

in a long wicker basket running down the side of the car. Holding the parasol

both hands, she started to whack Corny over the head with it.

"You're a rotten little so-and-so!" She screamed.

"You're a miserable, dried up little man!"

[Dinah

Sheridan says

that she was actually the one on the receiving end of Kay Kendall's outburst]

I thought she was joking. It was colossal fun seeing Corny

being brained. I roared my head off.

But it was no joke. It was genuine. Katie had really gone. She

was hysterical. The terrible cold weather, added to the normal tension of

filming, had got her down.

I shouldn't have laughed. In a few more days I was feeling the

same way myself.

|

|

|

Quentin

Falk: Olive Dodds, the Organisation's director of artists and regular confidante of her

charges, said that Kay Kendall spent hours with her "trying to persuade me

to get her out of the film, which they all thought, while shooting on it, would

be a disaster. The combination of the long filming, the many takes, changes in

script and very, very bad weather had put them all into the glooms. In my

view, it proved to be the one part that appeared to have been written for Kay

and Kay alone.

Following text from Eve Golden and Kim Kendall's

's "The

Brief, Madcap Life of Kay Kendall" ©

2002 The University Press of Kentucky. Finally, the

real story behind Kay Kendall's behavior during the

filming of Genevieve." |

Eve Golden and Kim

Kendall:

Kay

had more problems than Kenneth More realized: she had found out a week

or two into filming that she was pregnant. Kay took three days off [in

order to end the pregnancy] and came back to work much sooner than she

should have. Weak and anemic under the best of circumstances, she was in

no shape to withstand jostling in antique cars and sitting about in the

freezing cold. "She was really in a bad way," recalls Dinah Sheridan.

"She shouldn't have been back at all." |

| |

|

| Kenneth More:

Seven-eighths of the way through Genevieve we ran out of

money. In order for work to begin on a film these days, the financial

backing for it, known as the "guaranteed completion money," has to be put

up first. |

| |

|

|

If for any reason the producer goes

over his budget, more money is needed to finish the job. This might mean 20,000

pounds or more. Insurance companies, however, give protection against this, and

for a premium they will, if the worst happens, step in and help the producer by

supplying "end money," as it's called. They're on a pretty good wicket, I think,

and don't have to pay out very often.

An exception, though, was Corny. He always ran over. He

went on and on, persevering until he got what he believed was right. He never

compromised. He never cut anything out. He never shortened anything.

Eventually with Genevieve, we reached a stage where the

insurance company was financing us. It didn't like paying out. To save a bit

here and save a bit there, it had little men prowling around the studio,

switching off lights that weren't needed. During the final weeks shooting they

watched electricity meters like hawks. It was as bad as having the bailiffs in.

|

| |

Dinah Sheridan: In

February of 1953, we saw loops of the film in a darkened studio and had to

repeat our dialogue into a microphone. We each re-recorded our lines separately

- we weren't together. We had a reference tape recording that had been made

throughout the filming. When you re-recorded a line, you had to match the

original as closely as possible -- and we were out-of-doors; we were sniffing,

we were coughing... choking, probably -- and we had to do it exactly as it had

been. That wasn't easy at all. 80 to 85% of the dialogue in the film had to be

recreated on the soundstage. Dinah Sheridan: In

February of 1953, we saw loops of the film in a darkened studio and had to

repeat our dialogue into a microphone. We each re-recorded our lines separately

- we weren't together. We had a reference tape recording that had been made

throughout the filming. When you re-recorded a line, you had to match the

original as closely as possible -- and we were out-of-doors; we were sniffing,

we were coughing... choking, probably -- and we had to do it exactly as it had

been. That wasn't easy at all. 80 to 85% of the dialogue in the film had to be

recreated on the soundstage.

|

|

I was at home one day and they

telephoned and said, "We've got Kay here, doing her lines... and she can't

laugh. She is quite incapable of producing a natural hysterical laugh. Could you

come over to the studio and help her?" Much to my delight, I got an extra

day's pay to go over to Pinewood Studios - about a fifty-minute drive - and

produce, with Kay, hysterical laughter. Then I had to stop, and she had to go

on.

In the scene in the Brighton hotel

room, the loud argument between Alan and Wendy provokes an awful banging on the

wall from the very annoyed people next door. The sound of this banging was added

later. When they filmed the scene, I had to react to nothing. All I knew was

that it was in the script. Alan leaves for the garage; the banging starts up on

the wall again, and I take a brown paper bag, blow it up, and explode it onto

the wall. And then there's a scream from the other side of the wall --

obviously, I'd stopped the banging. What few people know is that during the

re-recording sessions, they asked me to perform the scream! So that's me

you're hearing from the other side!

|

| |

|

The film starts practically silent - you get no music at all right through

the first credit titles - then Larry Adler's music begins. |

Click the button above to hear Larry

Adler's "Theme From Genevieve" |

|

|

|

|

Wonderful,

simply marvelous music. Larry told me many years afterward (I didn't meet

him until many years afterward) how he was given the script and was asked

if he'd write the music. And he said yes, he would love to. He had got an

idea for it and he would absolutely love to. And they said, "How much do

you want?" And Larry named a price, and they said, 'But we've told you, we

don't have any money, we just want you to do the film." |

| |

|

|

And Larry said, yes, he'd love to do it, too, but he couldn't do it for nothing.

And so he lowered his price quite a bit. And they said, "Now, look, we said

we don't have any money!" And he said, oh dear, I really want to do

this, and I've got such a good idea for it... I'll do it for a two-and-a-half

percent interest in the film. Which made him the only one -- except for Henry

Cornelius and the Rank Organisation -- who got anything out of it at all. We got

2,500 pounds, and that was it - we've never had another penny. But Larry still

gets two-and-a-half percent!

Quentin

Falk:

As

if confirming the worst -- apparently, the "front office" didn't like

the finished film -- the opening at the Odeon, Leicester Square was, according

to Keith Robertson of Rank Film Distributors (now RFD's director of

administration), then still General Film Distributors, "a non-event."

It

was, at first, very coolly received.

|

It often happens that winners are not recognized as such at

first by the people close to them. Bill Rose tells of the day when he and Corny

were in the bar at Pinewood, anxiously awaiting the verdict of the "front

office" after the first showing. Earl St. John came in, put his arms around

their shoulders and said in the nicest possible way -- and he was, indeed, a

very kindly man -- something to the effect that they were not to be depressed;

he believed in them and they would surely make a good film sooner or laterChristopher

Challis:

The first showing of the completed film was in the preview theatre at

Technicolor. As the lights came up at the end, Earl St. John, the American head

of production, who had expressed little interest in the film during its making,

rose to his feet and observed to Henry, and the rest of us who made the movie,

'We may get a few car nuts to go along and see it in this country, but it won't

do business anywhere else.'

|

| |

|

Quentin

Falk:

But somehow, with the word-of-mouth, it

took off and the results were amazing. In those days it took about 18 months for

a film to go through the sequence of six-day bookings, three-day bookings,

Sunday nights...

"We

didn't let Genevieve go to Sunday nights, we put it out as a reissue

double bill with our other big hit, Doctor in the House. We'd always had

double feature programs, but it was always a first feature and a B-picture. This

was the first of its kind -- "the Doc and the Crock" -- and it proved

to be one of the most successful double programs we've ever put on."

Full

of now-classic moments like Kay Kendall's impromptu trumpet solo, the creaking

bed rocked by the chimes of the huge clock opposite, and More telling Kay to get out and

push the recalcitrant Spyker, not to mention

wonderful cameos by Geoffrey Keen as a traffic policeman and Joyce Grenfell as a

hotel proprietress, plus Larry Adler's fine harmonica score, no wonder Genevieve

was named Best British Film of 1953. It also, perhaps surprisingly for something

so quintessentially English, earned two Oscar nominations, for William Rose's

deft screenplay and Muir Matheson's music direction.

|

|

|

Sadly,

only one of the starring quartet is still alive today: Dinah

Sheridan. Kay

Kendall died in 1959 (a year after Henry Cornelius), John Gregson in 1975 and

Kenneth More in 1982. Sadly,

only one of the starring quartet is still alive today: Dinah

Sheridan. Kay

Kendall died in 1959 (a year after Henry Cornelius), John Gregson in 1975 and

Kenneth More in 1982.

As

Miss Sheridan reflected: "It's very sad. I'm very much the lone

survivor -- if you don't count Genevieve herself. She will be our epitaph."

Sir

Michael Balcon: Despite the variety of films we made over the years, I suppose

it is the comedies with which Ealing will always be identified. Even as late as

1967, an American correspondent of The Times, commenting on a letter from

a number of American governors, senators, congressman, chancellors of

universities, etc., on means of preserving the historic relationship between

[the United Kingdom and United States], said: "the old Ealing studio

comedies, which are still appearing on television late-night shows, have done

more for the relationship than any official program could have done."

|

| |

|

Corny and the enchanting Kay Kendall are, alas, dead long

before their time but Genevieve will remain in the hearts of all the fans

of their generation. Meanwhile Bill Rose, now a naturalized British subject, has

done a lot of work for Hollywood and has among his more recent credits such

important script as It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and Guess Who's

Coming to Dinner?, for which he deservedly won an Oscar, for the best

original screenplay, in 1968.

|

Genevieve was perhaps the most successful British comedy film ever

made -- written by an Ealing man and directed by another, but, alas, not at

Ealing! Genevieve was perhaps the most successful British comedy film ever

made -- written by an Ealing man and directed by another, but, alas, not at

Ealing!

One of the world's great

movies; one of the world's worst one-sheets: the American poster for

"Genevieve."

|

| |

|

[ Up ] [ Genevieve Rally July 2002 ] [ Models and More ] [ Bookshelf ] [ Genevieve Links ] [ Is This the Real Mr. McKim? ] [ What's Wrong Here? ] [ The 'Very Easy' Genevieve 50 Years On Quiz ] [ Genevieve Picture Gallery ] [ Music by Larry Adler ] [ Genevieve's History ] [ The Cast ] [ Filming Locations ] [ Making "Genevieve" ] [ London to Brighton 2000 ] [ Audio Clips ] [ Site Map ] [ Thanks ] [ Down Under ] |

|